Pints for the Planet: Griffin Claw saves grains from dumps, cuts carbon footprint

Griffin Claw Brewing in Birmingham is changing the brewery game by implementing multiple sustainable practices like sending their brewers’ grain to local farmers and recapturing CO2 to prevent it from entering the atmosphere.

Birmingham-based Griffin Claw Brewing Company offers freshly distilled beers and hard ciders to its local community. The company says it was always in its interest to invest in sustainable practices.

“We wanted to be part of the people, planet, profit movement,” says Pat Craddock, CFO of Griffin Claw.

The shift towards environmentally friendly practices in the brewing industry is growing, with other breweries across the U.S., like Alaskan Brewing Company, and locally like Griffin Claw, setting an industry standard.

Over the last five years, Griffin Claw has implemented sending their weekly spent grain, a mix of barley and other grains resembling a clump of oatmeal, to local farmers and recapturing their CO2 to use for their daily beer processes rather than it entering the atmosphere.

“Investing in sustainable brewing practices is critical to help improve long-term resource availability and reduce Griffin Claw’s footprint on the environment,” Craddock says. “It doesn’t hurt that many sustainable practices often result in cost savings once the investment is paid for.”

Using Spent Grain as Food for Cattle

When making any sort of beer or cider, the first step is to soak, or mull, the grain in water. Then the grain is mashed to convert the starches into sugar.

Then the liquid, also known as wort, is separated from the grain through a filter. Wort is important because it serves as food for the yeast, allowing the liquid to ferment and produce alcohol.

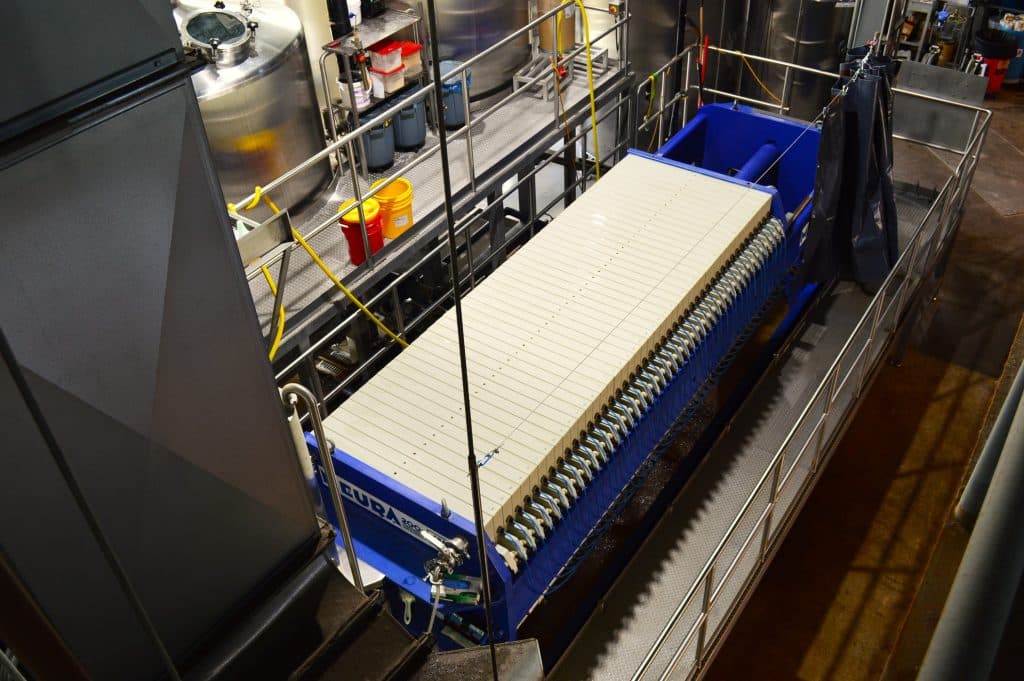

Griffin Claw uses a Meura mash filter, a custom-made, Belgian-based technology that produces 500 gallons of beer every 90 minutes.

“Every day we make two batches at 1,550 gallons in each barrel, so that’s 3,100 gallons of beer a day,” says Christopher Lasher, marketing director at Griffin Claw.

With the mash filter, they reduce the amount of water used in the typical brewing process because it’s able to push nearly all of the wort out of the grain, creating the need for less water and increasing the wort yield. This gives the beer a higher alcohol content and a stronger, tastier flavor.

“In the usual process, the wort yield is near 85%,” Craddock says. “But with the mash filter, we’re getting about 98%.”

Once the liquid is boiled with hops and fermented with yeast, it will create alcohol. But in that process, there is leftover grain, which they have found a solution for keeping out of landfills.

The spent grain is delivered to local farms, like Bower’s Farm School, which will use it to feed their cows, goats, and sheep. The partnership began when Griffin Claw supplied beer to Bower’s events, and over time, they found another way they could work together.

“The animals just love it,” says Paul Watkins, resident farmer at Bowers. “I’ve always had brewers’ grain, and I’ve always fed it on my farms as long as I had it available to me. ”

Brewers’ grain contributes to 85% of breweries’ waste, and six beers equal one pound of spent grain. Because spent grain can spoil quickly, being able to ship it to a farm only a mile away makes it even more sustainable.

“When we get it, it’s hot, it’s fresh,” Watkins says. “The spent grain is high in protein, like most feeds, but this is lower in carbohydrates.” He adds that the spent grain has been proven to improve cows’ metabolism, thereby increasing milk production.

But the most exciting thing for the farmer, Watkins says, is that it lowers costs. The brewers’ grain they get from Giffin Claw is nearly 25% cheaper than what the farm would typically buy.

The partnership also allows both Griffin Claw and Bowers to spread awareness of each other, which in turn helps the businesses grow.

“It checks all the boxes,” Watkins says.

Keeping the Air Clean with Carbon Recapturing

Inside the tank, where the beer has cooled after brewing, CO2, or Carbon Dioxide, is floating around needing to be released.

“If the CO2 wasn’t released, it would create so much pressure and the yeast would either choke out and die or the tank would explode,” Lasher says.

Oftentimes, that CO2 gets released into the atmosphere, increasing the amount of CO2 in the air, and too much Carbon Dioxide causes negative health impacts like elevated heart rate, dizziness, and headaches. But, CO2, when dissolved in a liquid, is essential for creating carbonation and for helping move beer.

During the COVID-19 Pandemic, there was a CO2 shortage, a still ongoing issue. To combat both issues, the brewery installed a Carbon Dioxide recapturing device called Cici, designed by Earthly Labs in 2020. This device not only captures CO2 but also purifies it, compresses it into a liquid, and stores it for later use.

“With the CO2 we used to bring in, it would come from a source that’s not entirely sustainable,” Lasher says. Now, with the recapturing device, they can truck in less CO2 and use it to help move beers from one tank to another.

Since its installation, the brewery has recycled over 30,000 pounds of CO2 from entering the atmosphere, equivalent to 561 trees. While they are proud to have made such an accomplishment, it wasn’t easy to achieve.

“Craft beer is in a tough spot, financially, at the moment — so although we encourage other breweries to look into sustainable practices such as CO2 recapture, it obviously has to fit into the budget,” Craddock says. “There are other, less expensive, sustainable/recycling measures breweries can incorporate, and although the impact may seem small, every little bit helps.”

In the future, the brewery hopes to add a baler to recycle cardboard and plastic wrap, a solar farm on the barrel house in Birmingham, and EV charging stations next to their barrel house, but it’s all about finding the right partners and doing what makes sense for the brewery.